Yesterday afternoon (December 6th, 2017), Finance Minister Philip Hammond sparked alarm and condemnation for suggesting that the UK’s stubbornly low productivity rate was due to the high employment rate and larger numbers of disabled workers. His exact quote was:

It is almost certainly the case that by increasing participation in the workforce, including far higher levels of participation by marginal groups and very high levels of engagement in the workforce, for example of disabled people – something we should be extremely proud of – may have had an impact on overall productivity measurements.

The problem is, there does not appear to be any evidence that this is actually the case, in the UK or elsewhere. Disability Rights UK, amongst others, has condemned Hammond’s comments, but I wanted to take a look at his claim that higher employment rates are responsible for the UK’s low productivity per hour of work compared to many other advanced economies. Please note, this is a blog post with a lot more math than most of the things we on this blog. My main point is that Hammond is incorrect, and that higher employment rates appears to lead to higher productivity, not lower.

I found employment data (the percentage of people aged 15-64 in work) and productivity (the average output to Gross Domestic Product per hour of work in 2010 Purchasing Power Parity US Dollars) for every OECD country (plus Lithuania, Russia and South Africa). This data covers 2005–2016. First, I created a plot to show the relationship between employment rate and productivity, for each country and year. The large blue line shows the linear relationship between employment and productivity, showing that countries with higher employment rates tend to have higher productivity rates. R2 is 0.216. The shorter red line is the trend just in the UK, where R2 is much lower, at 0.132.

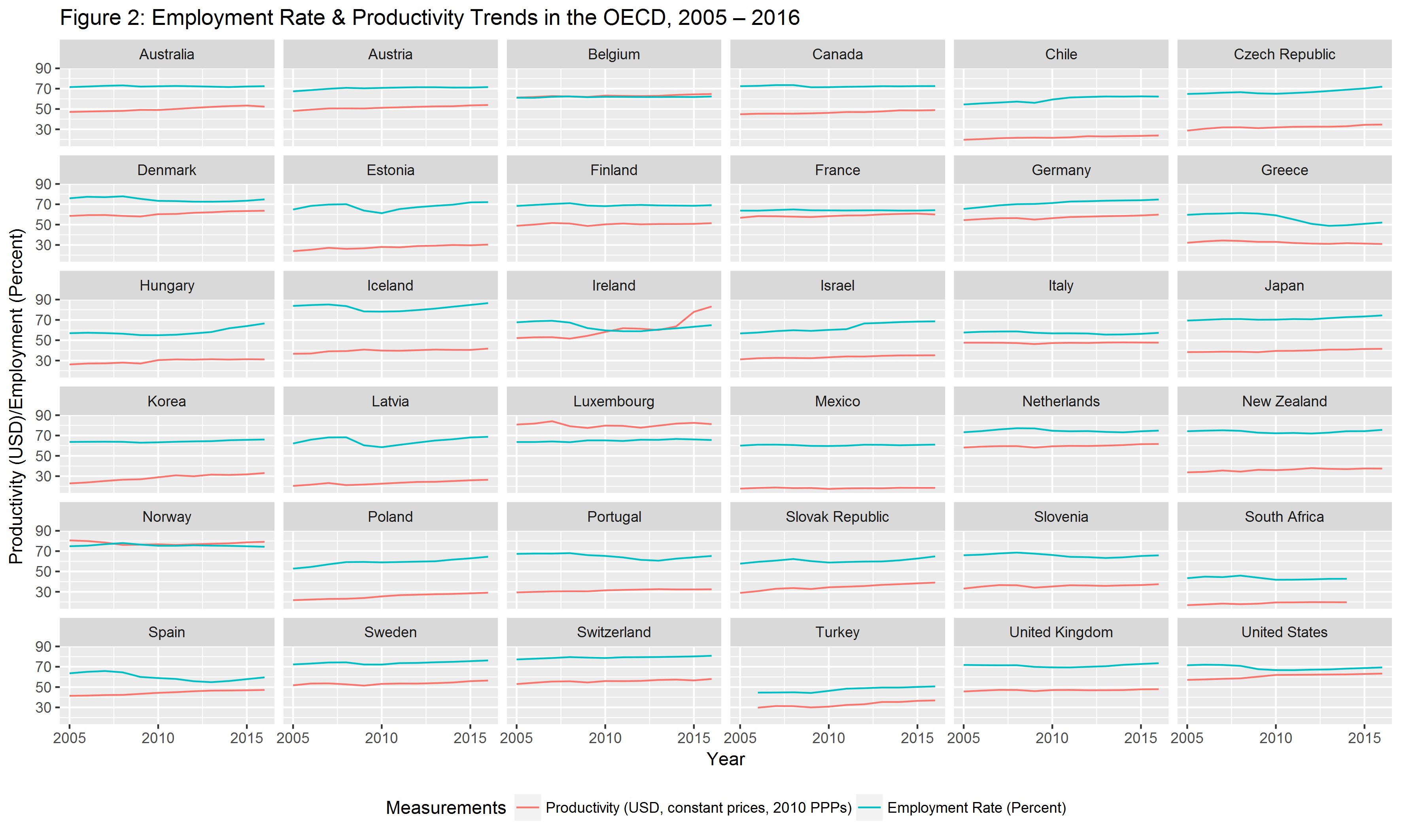

I’ve also produced graphs showing the trends in employment rates and productivity for each of the 36 countries I have data for. As you can see, there are no cases where large decreases in employment lead to large increases in productivity. For example, Greece saw a large decline in employment rates in the early 2010s, with little change in productivity, and Hungary’s employment rate has increased steadily over the past several years with virtually no change in productivity. Alternatively, Ireland has seen massive increases in productivity over the past several years, with much smaller increases in employment rates.

Now it gets very technical. I’ve created two regression models, Model 1 uses a fixed effects model to account for unobserved differences (heterogeneity) between different countries, while Model 2 is a simpler pooled effects model. In Model 1, higher employment positively correlates with higher productivity, although the coefficient is small (0.012) relative to the standard error (0.043), and it is not statistically significant. The fixed effects model suggests that, when accounting for underpinning economic structures, employment practices and other parameters, the connection between productivity and employment rates is effectively non-existent. The pooled model shows a much clearer relationship between employment rates and productivity – the predicted result of a one percent increase in employment rates is an extra $0.895 (USD) of GDP per hour of work. It does not account for other economic parameters that Model 1 suggests have a more meaningful impact on productivity, although it does not provide any evidence that increased employment reduces productivity.

What this all suggests is that Philip Hammond is incorrect that the cause of Britain’s low productivity rates is due to higher workforce participation by members of what Hammond calls “marginal groups”, including disabled people. For one thing, disabled people are only a small proportion of the workforce – about 11.4% of everyone in work. On an even more serious point, Hammond’s comments get in the way of his government’s admirable aim of getting a million more disabled people into work over the next decade. By assuming that disabled workers are inherently less productive than non-disabled workers, with no evidence to suggest this to be the case, Hammond provides cover for employers who don’t hire disabled applicants based on the erroneous belief that they will be less productive. Economic productivity, at least on a national level, is not about the characteristics of a country’s workers, but the opportunities they have in their work to make the best use of their skills and talents.

Notes

As always, code and data is available on GitHub, under an MIT License.

This blog was originally written for and published by Disability Rights UK